How one Chattanoogan Helped Women Get the Right to Vote

written by Kate Harrison Belz

9 Things to Know About Abby Crawford Milton, Chattanooga’s Suffragist Leader, and the Final Showdown for Women’s Voting Rights

Abby Crawford Milton (Tennessee State Archives)

On a sweltering August day in 1920,

a crowd packed into the Tennessee legislative chambers to learn the fate of American women’s voting rights. After more than 70 years of suffragist struggle, the 19th Amendment — which gave women the right to vote — had already been passed by Congress. But it required ratification from 36 states in order to be added to the U.S. Constitution. By 1920, 35 states had ratified the measure. Would Tennessee be the 36th, and seal the deal?

Sitting in the chamber, nervously listening to the roll call, was Chattanoogan Abby Crawford Milton. In just five years, she had transformed from newly-recruited suffragist to the President of the Tennessee League of Women Voters, and was a driving force behind the ratification campaign.

“I shall never be as thrilled by the turn of any event as I was at that moment when the roll call that settled the citizenship of American women was heard,” she later wrote. “It seemed too dramatic to happen in real life, with the real thrill of history making, not the excitement of stage or movies. Personally, I had rather have had a share in the battle for woman suffrage than any other world event.”

Yellow roses — a symbol of women’s suffrage — flew into the air, and Tennessee suffragists were hailed for clinching this culminating victory for women’s voting rights. But 100 years later, many of the women who fought for voting rights on local battlefronts have been forgotten. Who was Abby Crawford Milton, and what role did Chattanooga play in the fight for women’s suffrage?

1. She “didn’t even know how to spell suffrage” when she was first recruited to fight for women’s voting rights.

Abby was a relative latecomer to the suffrage movement. Looking back on her activist work, she would later say she became interested in the movement “almost by accident.”

Abby had always been exposed to politics. Her father was publisher of a Georgia newspaper, and Abby had attended college and even law school, though she never practiced law. But she was not interested in women’s suffrage until a fateful dinner in 1915. She was dining with a friend in the mezzanine of the Hotel Patten in Chattanooga (now Patten Towers) when some women approached the friend and implored her to become president of their suffrage association. Abby’s friend agreed to take the post on one condition: that Abby would be her vice president. “I didn’t know how to spell suffrage,” Abby later said. “I didn’t know the least about it. I thought I’d help these girls out by saying, ‘Well, I’ll go ahead and be your vice president.’ I didn’t know what I was getting into and believe me, it was some hot water because I forgot all about that for a week.”

2. One of the biggest obstacles she and other Tennessee suffragists faced was the “general indifference” of other Southern women.

“The women’s suffrage cause was the most unpopular cause ever before the American people. Awfully unpopular,” said Abby. “The men didn’t want us to vote. They didn’t want to be interfered with in their little setups in politics, and the women — they were just indifferent. The bulk of women didn’t care about anything about having the vote. The Southern women particularly. We yielded in all to our men. We had utter confidence in our Southern gentlemen. And we didn’t want to take away their big game. It was a big game — politics. The Southern states did not support the suffrage movement. Tennessee was in the doubtful column.”

3. She built on work that had been established by other Chattanooga women.

Abby may have been new to the suffrage movement, but a group of Chattanooga-area women had been fighting for women’s voting rights for years. Records of suffragist meetings in Chattanooga date back to the late 1880s. The most sustained effort was the Chattanooga Equal Suffrage League, started in 1911. Two of the members, cousins Margaret Ervin, Jr. and Catherine Wester, had traveled on a whim to a National Suffrage Convention and come home ready to organize in Chattanooga. Over the next several years, the cousins spearheaded local suffrage activity even as Margaret pursued an law school and Catherine a career in architecture. Abby would later work with both women.

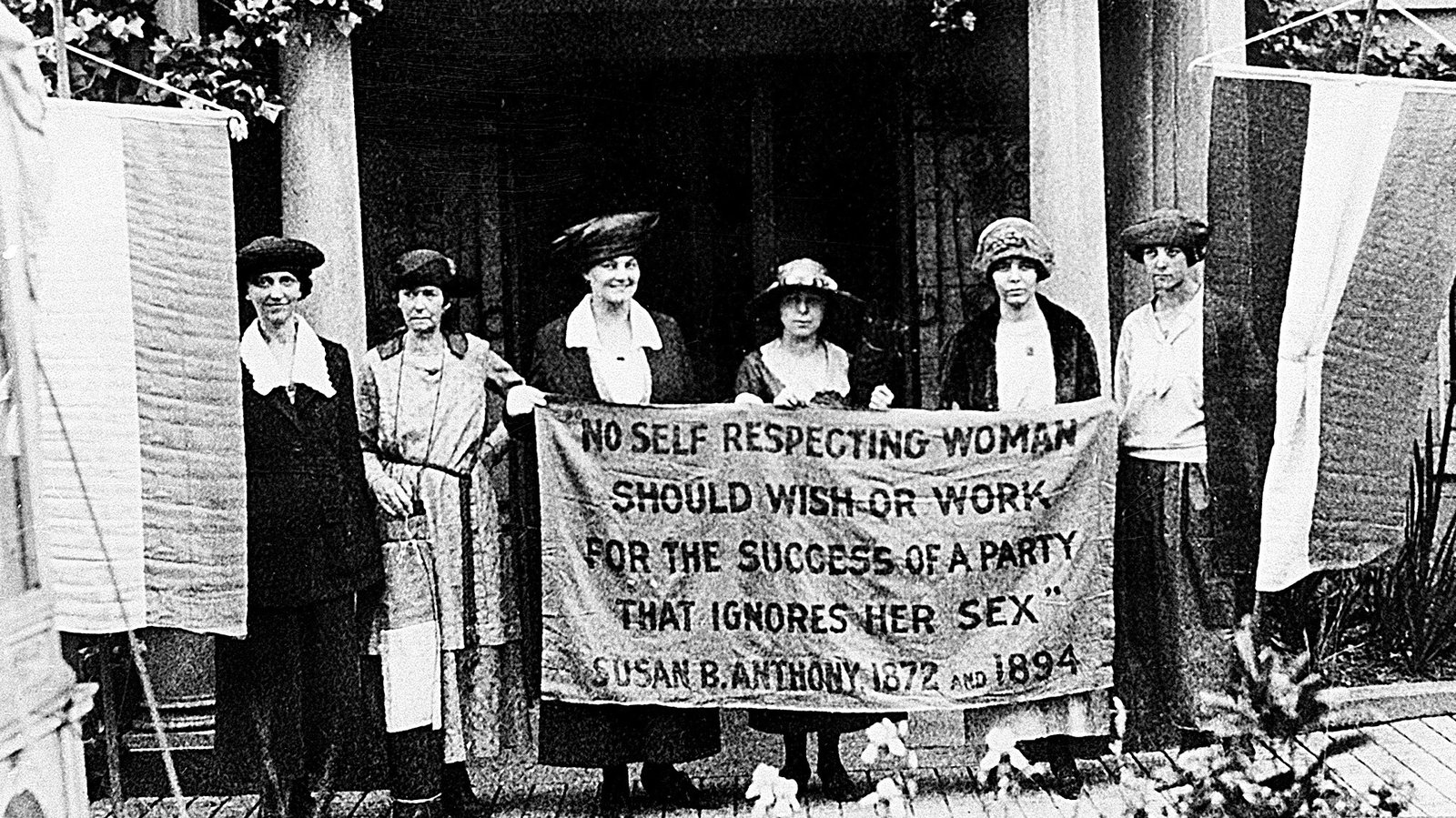

4. She worked to unify suffragist factions.

By the time Abby joined the effort, Tennessee women’s suffrage groups were splintered by bitter infighting. “We met at the Hurricane Hotel in Nashville and we were the biggest hurricane that place ever saw,” Abby described one quarrelsome meeting between dueling state suffrage organizations.

"...we were the biggest hurricane that place ever saw"

Abby led the opposing groups to merge, and the movement gained momentum, suffragists chalked up notable victories: In 1917, Lookout Mountain, Tenn. women became the first in the state to vote in a school board election.

A few years later, Abby became the first president of the newly-formed League of Women Voters of Tennessee. The statewide organization was laser-focused: by May of 1920, it was calling upon state lawmakers to ratify the 19th Amendment. Thanks to the sustained push from Abby and her fellow suffragists, the matter would soon be put to a vote in Nashville.

5. Abby’s husband, a Chattanooga newspaper publisher, was a key ally.

George Fort Milton met Abby Crawford while she was taking summer courses in Knoxville. “The first two or three times he proposed to me, I laughed at him,” Abby told one reporter. “Southern girls didn’t take men so seriously in those days and I don’t ever remember saying ‘yes’ formally. But when he told me we couldn’t get married until after he bought a new press for his paper, he convinced me he that he was an earnest man indeed.”

George also proved earnestly supportive of women’s right to vote. He helped organize a men’s club supporting women suffrage in Chattanooga, and he was the owner and publisher of the staunchly pro-suffrage Chattanooga News. “The papers helped us all they could, but they were opposed by other papers in the same town,” said Abby. The Chattanooga News’ rival, the Chattanooga Times, strongly opposed women’s suffrage.

“They were so vicious against me that I was scared that my husband would go down there with a little gun to settle with them,” Abby recalled years later.

(From “Thrill of History Making” - possibly available from Tennessee State Archives)

George Fort Milton, Sr. with wife Abby, their three daughters, and Joanie (last name unknown). (The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture)

Abby Crawford Milton is shown in a decorated car with suffrage supporters, as well as her three children, in front of her home in Chattanooga. ("The Thrill of History Making: Suffrage Memories of Abby Crawford Milton” in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly)

6. She took her young daughters along on her cross-state lobbying trips

Abby gave birth to three daughters during the height of the Tennessee women’s suffrage movement: Corinne, Sarah Anne (Sally) and Frances were all born between 1913 and 1918. On statewide canvassing trips, her daughters often rode with her.

Once asked if she was considered a “radical” in her time, Abby scoffed.

“Me? I was certainly not. I was just busy having babies.”

7. She called fight for ratification in Nashville “the fiercest legislative battle that was ever waged on this continent.”

Under pressure from the coordinated Tennessee women’s suffrage groups, Gov. Albert H. Roberts called a special session to vote on ratifying the 19th Amendment in August 1920.

As Tennessee was the final battleground for national ratification, lobbyists and activists from both camps descended upon Nashville. “The lobbyists were there, all the opposition that met the suffrage cause in thirty-five ratified states were there against Tennessee,” Milton said.

Both suffragists and anti-suffragists posted up at Nashville’s Hermitage Hotel, which was draped in banners and filled with bushels of yellow and red roses — yellow for suffragists, and red for anti-suffragists. Legislators donned rose boutonnieres displaying their loyalties, causing the special session to be dubbed “The War of the Roses.” Liquor flowed in the lobby, and fistfights broke out as tempers ran high and dealmaking came down to the wire.

8. The decisive vote was cast by a man who listened to his mother. Abby Milton made sure he got re-elected.

As the legislation worked its way through the senate and the house, voting reached a deadlock and a victory for suffrage doubtful. But the tide turned on August 18, when young McMinn County lawmaker Harry Burn shocked everyone by changing his “nay” to an “aye” on the final ballot for ratification. Burn later revealed he had received a letter from his mother that morning, urging him to “vote for suffrage!” The measure carried, and history was made.

Burn paid for his decision later, as his fellow Republicans in his district turned against him and refused to support him when he ran for a second term. Hearing that Burn was in trouble, Abby galvanized newly-empowered Democratic women in Burn’s district and urged them to cross party lines to support him. Carried by these women’s votes, Burn was re-elected.

9. She remained an activist and author, and lived to be 110.

After ratification, Abby — or “Miss Abby,” as she later became known to Chattanoogans — remained active in politics and advocacy work. She helped campaign for Democratic presidential candidate William Gibbs McAdoo, seconding his Democratic presidential nomination in 1924. She lobbied for the establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1926, and made an unsuccessful bid for state senate in 1930.

She also had a successful career as an author and poet, publishing several volumes of poetry, including a volume of poetry centered on Lookout Mountain.

Abby moved to Clearwater, Florida in the late 1940s, but never developed a taste for Florida politics. “I’ve never been interested in Florida politics the way I was in Tennessee,” she said. “Tennessee is decisive and strategic … being in the middle of our United State has a great deal to do with it.”

She lived to 110, with Chattanooga newspapers marking each birthday with interviews. She died in 1991.

Sources:

- Bucy, Carole Stanford. "The Thrill of History Making": Suffrage Memories of Abby Crawford Milton." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 55, no. 5 (Fall 1996): 224-39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42628433.

- Galletta, Jan. "Abby Milton: Glowing Great at 108." Chattanooga News-Free Press (Chattanooga, TN), February 17, 1989. Chattanooga Public Library local archives.

- Galletta, Jan. "Secrets of a Long and Active Life.” Chattanooga News-Free Press (Chattanooga, TN), February 2, 1986. Chattanooga Public Library local archives

- Graham, Kay Baker. "Abby Crawford, Advocate for Women." Chattanooga Times Free Press (Chattanooga, TN), November 22, 2015. Chattanooga Public Library local archives.

- Miller, Donna. “More than the Vote.” Dec. 15 1986. Chattanooga Public Library local archives.

- "Political Leader, Poet Abby Milton, 110, Dies." Chattanooga News-Free Press (Chattanooga, TN), May 5, 1991.

- Yellin, Carol Lynn, Janann Sherman, Ilene J. Cornwell, Don Sundquist, and Martha Sundquist. The perfect 36: Tennessee delivers woman suffrage. Memphis, Tennessee: Vote 70 Press, 2016.